“I have always been more interested in experiment, than in accomplishment.” – Orson Welles

“I have always been more interested in experiment, than in accomplishment.” – Orson Welles

2014 looks to be a very exciting year around my house. Professionally, I’m poised to make a big change in order to tackle some long contemplated goals. I will be leaving UBC Faculty of Law after 14-1/2 years in June 2014, and am looking forward both to the next 5 months of transition time which will allow me to complete some long term projects and to the 6 months of new projects that will follow. In personal terms, the year might best be characterized simply by saying that all three of my daughters will be travelling to their own new adventures in the far corners of the world (Poland, Ghana and Philadelphia!). And with my own transition happening at just the right time … I may just get the chance to visit them there.

CoRe Jolts will be receiving a few jolts from a few projects connected to my transition plans, so you can expect:

- Posts that reflect the work I am doing with Carrie Gallant at CreativityZone,

- Development of Impasse Breaking Cards, and

- A Game Jam!

Join me in any or all of these projects!

Blog posts – MBTI series

In late November, Carrie Gallant and I led a workshop on advanced applications of the MBTI to conflict resolution. We focused on understanding possible uses of the Step II instrument for conflict resolution practitioners, and on exploring “Jungian functions” in more detail than one normally can in an introductory workshop. In respect of the latter topic, we specifically looked at the different ways that we collect data and the different ways that we make decisions. The discussion led me to spend some time over the vacation generating ideas for impasse breaking based entirely in each of these eight functions (e.g. I began with a list of impasse breaking ideas that reflect Extraverted Sensing, then generated a list of tools that reflect Introverted Sensing, etc.). I plan to share these ideas in two ways: I will blog about each of the eight Jungian functions and ideas derived from an understanding of that function, and I will incorporate many more of the ideas into the first set of impasse breaking cards for the project immediately below.

Impasse Breaking Cards

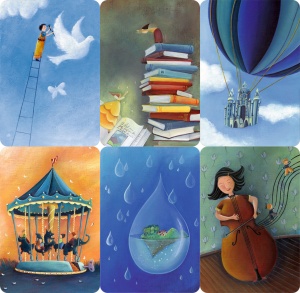

I have been intending to collect impasse breaking ideas into cards specifically designed for use in mediation, and this is the year I intend to create that deck. In fact, I have given myself a deadline of March 29th for completion of a prototype because I have committed to present the deck at the NWDR Conference in Seattle! You can see more details about this project on the Impasse Cards page. Check out the focus group sessions there and consider joining me in any of the testing sessions in the next two months.

Game Jam

I wrote about my interest in collaborative board games last summer. And now I’m planning to hold a Game Jam for Collaborative Professionals in order to bring together like-minded, but differently skilled, folks to create more collaborative games. I’ve set aside May 9th-11th for the event. If you’re interested in a weekend of fun and creation, save the date! And let me know that you’d like to attend.

Jolt for Mediators and Mediations:

Jolt for Mediators and Mediations:

Since this is a planning-for-the-year post, I’ve decided to offer a New Year’s jolt despite the date. (I will note that while my planning may have been triggered by the start of 2014, the post comes just before Chinese New Year, so still might pass as timely…)

#3Words Exercise

You may be familiar with the Three Words Concept. Chris Brogan and C.C. Chapman have each contributed to the idea of coming up with three words as a focus for the new year, as opposed to resolutions. It was Jason Dykstra’s 2014 post, however, that inspired me to finally take a stab at choosing and blogging about my own words. I admit, I was particularly taken by Jason’s creativity in applying his words, as opposed to the words themselves. His approach reminded me of exercises in the use of symbolism or combinational creativity to shake up one’s thinking. Jason’s word descriptions made it easy to imagine using this exercise as a jolt for mediators and as a jolt for mediation.

For Mediators:

The #3Words exercise can be a jolt for mediators or other dispute resolution professionals in the same way that it is intended to be a New Year’s jolt for anyone looking to shift gears. Wanting to improve your practice? Use the #3Words technique for self-reflection to guide your progress. You might focus on aspects of your work that you struggle with and wish to improve (e.g. self-reflection, listening, silence, etc.) or you might focus on business development and kickstarting an exploration of a new practice area (e.g. connect, system, leap, etc.)

And, of course, there’s no reason you can only think of focus words for the year. Why not consider focus words for a single mediation? If you’ve come from a difficult mediation, you’re probably already reflecting to some degree on whether there was something you might have done differently. Or you’ve co-mediated with someone and observed an entirely different approach that you’d like to add to your toolbox. And for that matter, what about those mediations where everything seems to happen without any effort on your part: are there aspects of those mediations that you want to carry forward into your next session? Why not think about three words immediately following one mediation that will be points of focus for your next mediation?

For Mediations:

Alternatively, in a mediation (and perhaps in a strategic planning session or when dealmaking), consider a #3Words list as a means of focusing parties on joint goals. We often assist parties to generate lists of interests or criteria for settlement; why not consider instead a list of three words to guide the discussion, or three words that reflect for an individual party her goals for settlement or his hopes for the future, or three words that capture the type of process that parties wish to pursue in their discussions? Such exercises might well assist parties to shift gears into a more reflective and problem-solving discussion, and might be easier to launch than a discussion of individual interests where parties are especially distrustful or uncomfortable with speaking directly about their own wishes.

My 3 Words for 2014

It seems appropriate to share my own three words for the year: Experiment, Delve and Concatenate. And yes, they are all verbs even if I had to force one of them to be. For me, 2014 involves doing, so my words are doing words.

- Experiment

I am not typically shy to experiment, so may not need this word to remind me to do so. I have chosen it instead to reinforce that experimenting is a positive aspect of my current work life that I want to retain. I may have to be more creative in developing opportunities to truly experiment outside of the academic world.

-

Photo: Ruth Flickr Meerkats “delving”

Delve

Clearly this will be a year to explore, and my list should include a word to recognize that fact. But explore doesn’t resonate the way delve does. Delve requires more digging, more extended effort. I’ll be delving.

- Concatenate

Much more commonly seen in the form “concatenation”, concatenate really is a verb – just one that doesn’t get much play. But I love the notion of combining that it evokes. My professional life has always concatenated a series of ideas, experiments, and explorations, and I am excited to continue concatenating this year!